The Story of the Soviet Z80 Processor

Before we get into the fascinating story of the Soviet (specifically the Angstrem) Z80 clone it’s good to understand a bit about the IC industry in the USSR. There were many state run institutions within the USSR that were tasked with making IC’s. These included analogs of various western parts, some with additional enhancements, as well as domestically designed parts. In some ways these institutions competed, it was a matter of pride, and funding to come out with new and better designs, all within the confines of the Soviet system. There were also the various Warsaw Pact countries (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania), that were aligned with the USSR but not part of it. These countries had their own IC production, outside of the auspices and direction of the USSR. They mainly supplied their own local markets (or within other Warsaw Pact countries) but also on occasion provided ICs to the USSR proper, though one would assume an assortment of bureaucratic paperwork was needed for such transfers.

Before we get into the fascinating story of the Soviet (specifically the Angstrem) Z80 clone it’s good to understand a bit about the IC industry in the USSR. There were many state run institutions within the USSR that were tasked with making IC’s. These included analogs of various western parts, some with additional enhancements, as well as domestically designed parts. In some ways these institutions competed, it was a matter of pride, and funding to come out with new and better designs, all within the confines of the Soviet system. There were also the various Warsaw Pact countries (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania), that were aligned with the USSR but not part of it. These countries had their own IC production, outside of the auspices and direction of the USSR. They mainly supplied their own local markets (or within other Warsaw Pact countries) but also on occasion provided ICs to the USSR proper, though one would assume an assortment of bureaucratic paperwork was needed for such transfers.

This resulted in some countries developing similar devices, at rather different times, or different countries focusing on different designs. East Germany was all in on the Z80, Romania, Poland and Czechoslovakia made clones of the 8080, Bulgaria, the 6800 and 6502. They were though, seperate from the USSR’s own institutional system, so while East Germany had a working Z80 in the early 1980’s the USSR did not. It is this distinction we will focus on today

This article is largely from guest author Vladimir Yakovlev, translated from Russian, and edited/expanded by me.

By the end of the 80s – beginning of the 90s, clones of the British Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer, a simple, cheap computer with a huge library of games originally released in 1982, were being distributed in the USSR. The “strapping” of the central processor instead of the original ULA microcircuit was done on small logic microcircuits of the 555 (74LS) series and the like, but the Z80 itself had to be bought from abroad. Naturally, the thought arose, to start making the processor yourself. After all, the processor itself, developed in 1976 for the microelectronic industry, was not too complicated.

In 1990, the development of an analogue of the Z80 was organized in Zelenograd near Moscow at the Scientific Research Institute of Precise Technology (NIITT) and the “Angstrem” plant. Initially, Zelenograd was conceived as a center of the textile industry, but was later reoriented to the development of electronics and microelectronics by Nikita Kruschev after he visited Silicon Valley (California, USA) in 1959. To this day, Zelenograd has retained the status of a scientific center and the informal name “Russian Silicon Valley”.

The chief designer was appointed Yuri Otrokhov, who had previously led similar developments. Otrokhov, who served as a tanker in his youth (military service being mandatory in the USSR), called the project the T34 microprocessor.

Otrokhov: “T-34VM1 is the internal designation of the KR1858VM1 processor, assigned by me at the stage of development and production in honor of my first tank, on which I learned to drive.”

Here is one of the versions of the creation of the clone, outlined by one of the employees of NIITT at that time, Boris Malashevich [1]:

“Otrokhov, like his colleagues in the department, knew how to develop original microprocessors, but they had not yet had to reproduce analogs. Therefore, the developers included specialists from NIITT divisions who are able to restore the electrical circuit of the IC according to its topology. For 9 months after four iterations, they managed to make an NMOS microprocessor T34VM1 (KM1858VM1, KR1858VM1) – a complete analogue of the Z80A microprocessor, to be made using a 2-micron technology” (The original Zilog version was on a 4 micron process).

While Otrokhov and his team worked at Angstrem to make a NMOS Z80, a similar team was working at ‘Transistor’ in Minsk Belarus to make a CMOS version, later known as the KR1858VM3.

Due to the incredible popularity and demand for the Z80, many analogue manufacturers worked without a license, so in total less than half of all Z-80 produced were licensed products from Zilog or its official partners (SGS, Mostek, etc).

From an interview with the creators of the Z80 [2]:

Faggin: Yes, we were concerned about others copying the Z80. So I was trying to figure what we could

do that that would be effective, and that’s when I came across an idea that if we use the depletion load

the mask that doesn’t leave any trace, then I could create depletion load devices that look like

enhancement mode devices. And by doing that we could trick the customer into believing that a certain

logic was implemented, when it was not. Then I told Shima, “Shima, this is the idea how to implement

traps. Put traps, you know, figure out how to do the worst possible traps that you can imagine,” and then

Shima with his mind, that was steel mind, was able to actually figure out a bunch of traps that he could

talk about.

Shima: I didn’t count [on] talking about that mostly. I placed six traps for stopping the copy of the layout

by the copy maker. And one transistor was added to existing enhancement transistors. And I added a

transistor looks like an enhancement transistor. But if transistors are set to be always on state by the ion

implantations, it has a drastic effect on very much. I heard from NEC later the copy maker delayed the

announcement of Z80 compatible product for about six months. That is what I got from NEC. And finally

a total transistor of Z80 became 8,200 while a total of transistor of 8080 was 4,800.

In the course of the design, due to the fact that the development team had specialists in both the creation of new ICs and the reproduction of analogs, Zilog’s tricks aimed at copy protection were identified and decrypted. For example, the topologist saw the 3-Input-NAND Gate element, but this element worked as 2-Input-NAND Gate. The topology and layout of the resulting clone was different, but the functionality did not differ from the original. At first, it was possible to identify such traps, making sure that the circuit was inoperable, only by examining the circuit elements inside the die using probe analyzers. But, having understood the principle of constructing traps, a mechanism for their detection was also developed. As a result, it was possible to make a full-fledged analog of the Z80, although the electrical circuit and topology of the T34MV1 had some differences.

The German Connection

It is known that the T34VM1 and subsequent ones, produced in the USSR, contain differences in undocumented commands, which exactly coincides with the logic of the U880 processor from East Germany. They do not set the CY flag when the OUTI command is executed (by the result of adding the number issued to the port and the value of the L register after the operation), and the hidden system bus register, the contents of which are available through the undocumented flags F3 and F5, have a different logic of operation.

Microprocessor from the German Democratic Republic.

Мanufactured by VEB Mikroelektronik “Karl Marx” Erfurt (abbreviated as MME; part of Kombinat Mikroelektronik Erfurt) in the German Democratic Republic.

And here is the microprocessor manufactured by the Angstrem plant.

Firstly, the case of the microcircuit is clearly Soviet, produced by the Semiconductor Devices Plant (Yoshkar-Ola) [3]. And secondly, the marking features are typical for the products of Zelenograd “Angstrem”.

After some time, the marking was changed to a more familiar one.

Ceramic package of the T34VM1 Z80-compatible processor, manufactured in the Soviet Union/Russia by Angstrem in 1992 and later years. The ‘ОП’ marking means “experimental batch”.

Sometimes there were more exotic markings.

The markings suggest an 8MHz version, well within what a 2 micron process is capable of

The Angstrem plant also produced many microprocessors in plastic.

KR1858VM1 manufactured by the Angstrem plant, produced up to 9303 inclusive, also is marked ‘ОП’. The example issued 9312, no longer has such a mark.

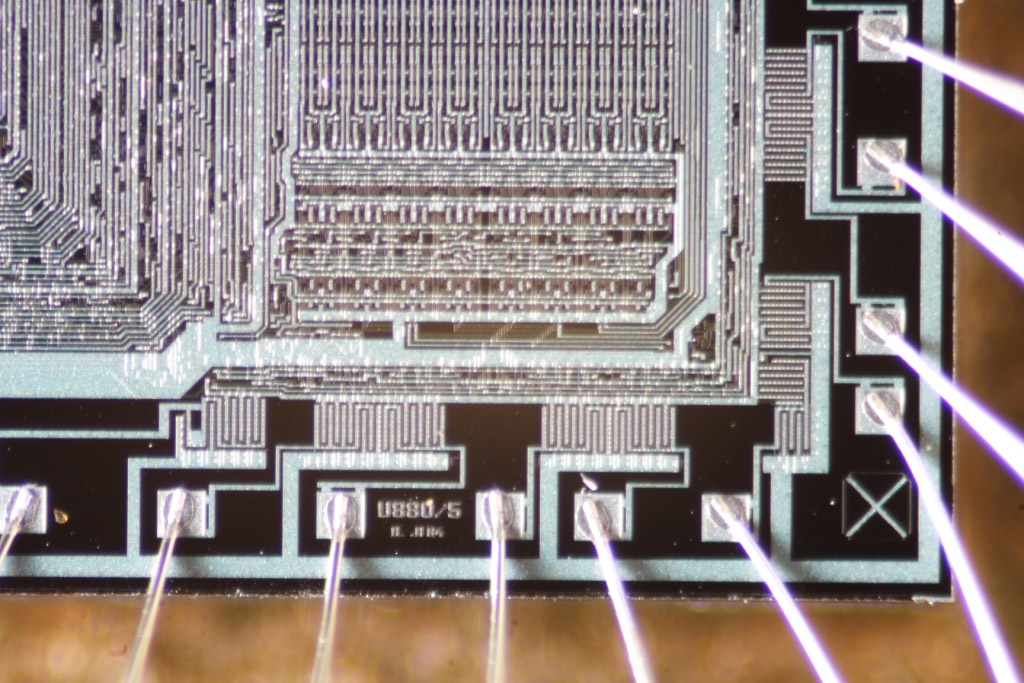

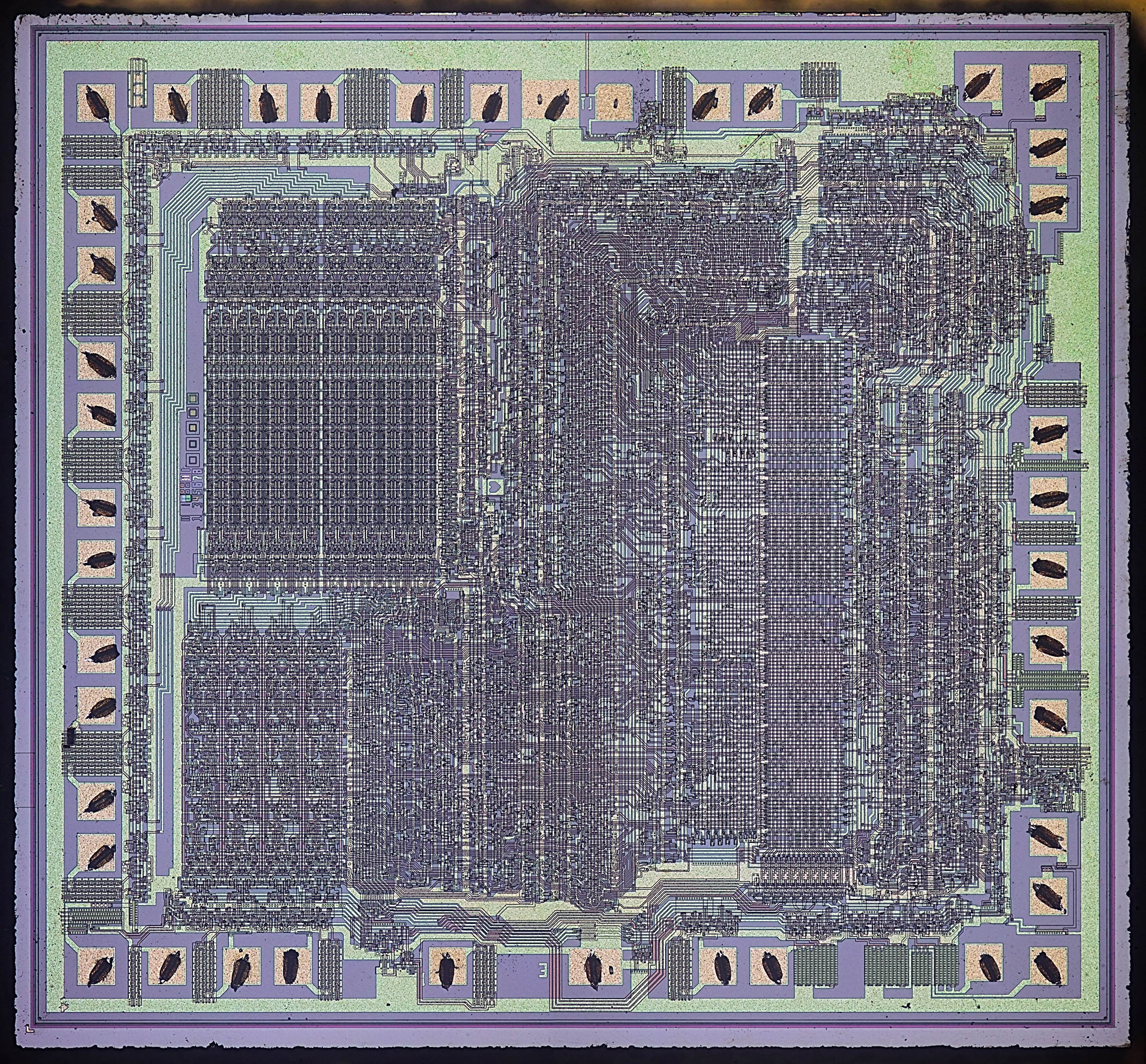

Looking at the die of an early T34 marked processor it is noted that there is an inscription “U880 / 5” on the T34VM1 [4]

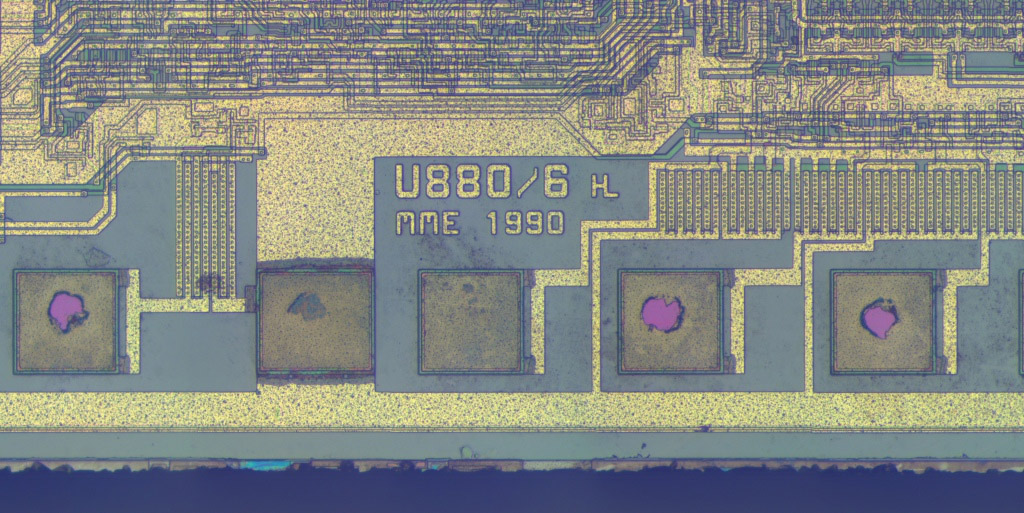

KR1858VM1 die marked MME 1990 Rev 6 – A ~1.6x shrink of the previous version allowed speeds of up to 8MHz

The die of a later KR1858VM1 contains the inscriptions “U880 / 6” [5]

The topologists had to copy exactly the East German version one-to-one, except in places where it did not comply with the topological restrictions associated with the NMOS manufacturing technology available at the Angstrem plant. Which was eventually done. And the products themselves were made from crystals obtained from MME. Indeed, since Soviet times, there have been quite close relationships between MME and NIITT.

On October 3, 1990, the unification of Germany took place. Stocks of finished dies had been accumulated at MME. But the question of patent purity immediately appeared (now joining the West Zilog could have pressed claims of copyright infringement, they ended up not, and Germany continued to make the unlicensed U880 with Zilog even using Thesys as a distributor). Most likely the dies and photomasks were transferred to the Soviet Union even before this event. This allowed Angstrem to use MME dies while they finished work on their own version.

Towards the end of 1993 Angstrem began making clones using its own photomasks. The inscription U880 disappeared from the die. An image of a heart appeared in the center.

Angstrem continued to make Z80s through the 1990’s.

Other former Soviet institutions also made clones of the Z80, including Kvazar (in Kiev Ukraine) and Electronica (now VSP-Mikron). Details on these are lacking greatly, but looking at a die from an early 1993 version of a Electronica T34 we see a very similar die to that of the Angstrem, including the heart in the middle of it as well. Dies of the Kvazar look similar to the early Angstrem versions, but lack the heart in the middle of the die. It’s possible Angstrem supplied dies (or masks) to other institutions as well.

Unfortunately Angstrem is no more, being hit hard by US Sanctions it was taken over by the VEB bank in 2019.

If you have more info/details that can further fill in some of the blanks (especially about Electronica/Kvazar versions) drpop us a line.

[1]. https://www.electronics.ru/journal/article/477

[2]. Three founding members of Intel microprocessor spin-out Zilog Corporation, Federico Faggin, Masatoshi Shima and Ralph Ungermann describe the early days of the company and the development and marketing of the Z80 microprocessor that became one of the highest volume and longest-lived architectures in the industry.

https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102658073

[3]. https://zpp12.ru/products/metallokeramicheskie_korpusa_i_osnovaniya/

[4]. https://zeptobars.com/en/read/t34vm1-z80-angstrem-mme

[5]. https://zeptobars.com/en/read/KR1858VM1-Z80-MME-Angstrem

April 23rd, 2024 at 12:53 pm

thanks for the details !!! such an amazing story !!!!

thanks again…