March 11th, 2014 ~ by admin

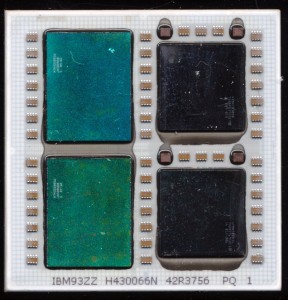

IBM z800 MCM

Mainframes are the workhorses of the computing industry. They process transactions for about every industry, and handle the brunt of the economy. Their MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures) is measured in decades (typically 20-50 years). A comparison to a home computer is hard to make, they are in an entirely different league, playing an entirely different game.

Data Intense vs. CPU Intense

Mainframe processors such as these work in what is referred to as ‘Data Intensive’ computing environments. This is different from multi-cored processing that focuses on ‘CPU Intensive’ computing. CPU intense has a relatively small data set, but most perform a lot of work on that set of data, or do the same instruction on a set of data (such as graphics). CPU Intense processing can often be sped up with the addition of more processing cores. Data Intense processing does not see as much benefit from adding cores. Its biggest bottleneck is accessing the data, thus the System z tends to have VERY large caches, and very high bandwidth memory. They typically operate on transactional type data, where the processing has to operate in a certain order (A has to be done before B which has to finish before C etc).

IBM was one of the first, and continues to be one of the largest suppliers of such systems. Starting with the System/360 introduced in 1964 to the zSeries today. The zSeries was first launched in 2000 with the z900, a significant upgrade from the System/390. Data addressing was moved to 64-bits (from 31 bits) yet backwards compatibility (all the way back to the 360) is maintained. The z900 ran at 775MHz and was built with a 35 die MCM containing 20 Processing Units (PUs) and 32MB of L2 Cache.

Read More »

March 6th, 2014 ~ by admin

ARM 701 mis-print on the left

We recently received several Remote Server management cards, powered by the Agilent (spun off of HP in 1999) N2530 SoC. This SoC provides the processing for remotely administering, and managing servers. At its hearts is an ARM processor running at 33MHz. Proudly marked on the chip, is ‘ARM 701 POWERED.’ There is one problem, there never was an ARM701 processor core. The N2530 is in fact powered by an ARM710. A typo was made when marked the Rev D chips, and later fixed on the Revision E. I have not yet received an example of a Rev C (or earlier) to see if they too have this error, but E and later certainly did not. The Agilent N2530 was used for many years in the early 2000’s on cards by Dell, Fujitsu, and IBM (and likely others). Essentially forming a computer within a computer, these cards often had their own graphics support (ATI Mobility Radeon, among others) as well as support for CD-ROMs, hard drives, LAN (for access) and everything else you would find in a stand alone computer. Typically they could remote start, reboot, and power down servers, all over a network connection.

February 18th, 2014 ~ by admin

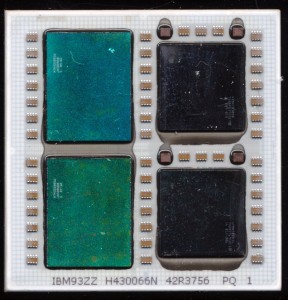

IBM POWER5+ QCM – 4 dies, 8 cores, and 72MB of L3 Cache

When the POWER5 processor was released in 2004 it was made in two versions, a DCM (Dual Chip Module) containing a POWER5 die and its 36MB L3 cache die, as well as a MCM containing 4 POWER5 die and 4 L3 cache dies totaling 144MB. The POWER5 is a dual core processor, thus the DCM was a dual core, and the MCM an 8 core processor. The POWER5 contains 276 million transistors and was made on a 130nm CMOS9S process.

In 2005 IBM shrank the POWER5 onto a 90nm CMOS10S manufacturing process resulting in the POWER5+. This allowed speeds to increase to 2.3GHz from the previous max of 1.9GHz. The main benefit from the process shrink was less power draw, and thus less heat. This allowed IBM to make the POWER5+ in a QCM (Quad Chip Module) as well as the previous form factors. The QCM ran at up to 1.8GHz and contained a pair of POWER5+ dies and 72MB of L3 Cache.

The POWER5+ was more then a die shrink, IBM reworked much of the POWER5 to improve performance, adding new floating point instructions, doubling the TLB size, improved SMP support, and an enhanced memory controller to mention just a few.

The result? A much improved processor and a very fine looking QCM.

February 9th, 2014 ~ by admin

DEC 1611H 21-15579 – LSI-11 RALU (MCP-1600)

Fully 10 years before Western Digital released their first hard drive, they made processors, calculator chips, Floppy Disk controllers and a host of other IC’s. Western Digital began in 1970 making primarily calculator chips. In 1976 they announced the multi-chip MCP-1600 processor. This was an implementation of the PDP-11 minicomputer in silicon. It consisted of a CP1611 Register/ALU chip, a CP1621 control chip and either 2 or 4 CP1631 512x 22bit MICROMs that contained the microcode implementation of the PDP-11 architecture. Physically this was an 8-bit design, but clever microcode programming allowed it to function as a 16-bit processor. Use of microcode allowed it to also implement floating point support, a very new concept in hardware in 1976. The MCP-1600 was used in DECs LSI-11 microcomputer among others.

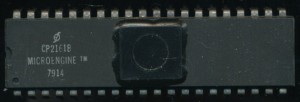

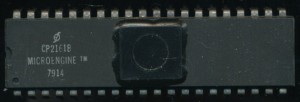

Western Digital CP2161B – 1979 Pascal Control Chip

Having the microcode separate from the ALU/Control didn’t help with board layout or cost, but it did provide a very flexible platform to implement other architectures on. In the late 1970s UCSD (University of California in San Diego) was working on a project, led by Kenneth Bowles, to make a portable version of the Pascal programming language, a version that could run on multiple hardware platforms, very similar to how Java has become today. The code was compiled to a ‘p-code’ or pseudo code that could them be executed by a virtual machine onto whatever hardware. Typically this virtual machine would be implemented in software, however the design of the MCP-1600 was such that it could be implemented in hardware, or rather microcode. Thus in 1978, the WDC MICROENGINE was born. This was to be a 5 chip set (original documentation states 4, but it ended up being 5) that consisted of the CP2151 Data chip (if you have a CP2151 you would like to donate, let us know) , the CP2161 Control chip, and 3 512 x 22 bit MICROMs which contained the microcode to directly execute UCSD Pascal on the data chip. The CP2151 was no different from the CP1611 of the MCP-1600 chipset and could be interchanged.

Read More »

January 17th, 2014 ~ by admin

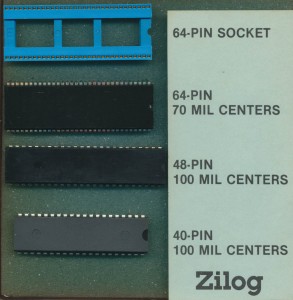

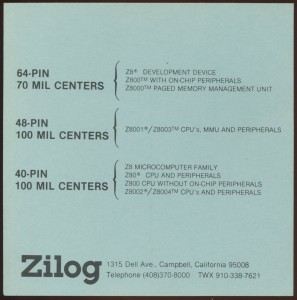

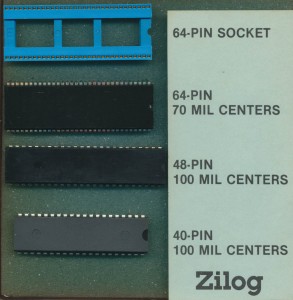

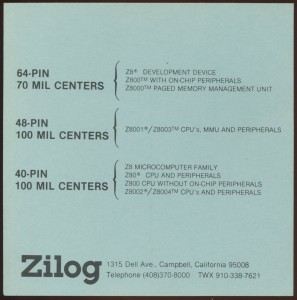

Zilog Packages available in 1985

Last week we showed you an educational kit from Zilog showing the process involved in making and assembling a Z80 processor, from polished wafer to packaging. Zilog also made a kit for marketing the various packages used. This kit contains a shrink DIP 64 pin socket, a shrink DIP 64pin package, a 48 pin DIP and 40 pin DIP, all the common packages used at the time.

Zilog Packages – Z8 Z80 Z800 and Z8000

At the time is a little hard to track down as no date is provided with this kit. We can get very close though looking at the back where Zilog lists which devices are available in these packages. The usual Z80 and Z8000 series are both there as well as the Z8 microcontroller family. The one odd-ball is the Zilog Z800. The Z800 was an upgraded Z80 released in 1985, adding on chip cache an MMU and a vastly expanded instruction set (over 2000 instruction/addressing modes). It was wholly unsuccessful partly do to bad marketing by Zilog, and partly because it did more then it needed to. It never entered mass production, and by 1986 Zilog has redesigned it, converted the design to CMOS (from NMOS) and released it as the Z280 which met the same fate as the Z800. It seemed that making an overly complicated Z80 wasn’t what the market wanted. THe Z180 (designed by Hitachi) and the Zilog eZ80 (released in 2001), have enjoyed much wider success, mainly because they kept closer to the simplicity of the original Z80.

So when was this kit put together? Likely 1985, as the Z800 was nly talked about for a few months before quietly being put away.

January 9th, 2014 ~ by admin

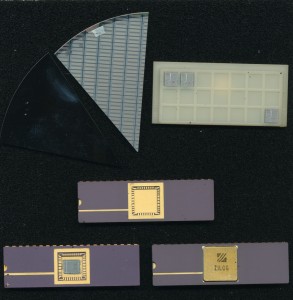

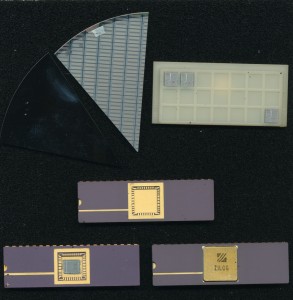

Zilog Z-80 Kit – Click for full size

Here is a neat kit from Zilog. Its an Educational Kit showing some of the steps of producing a Z-80 processor. It includes:

- A raw polished wafer slice before any etching has occured. This is what a processor starts out with (sliced from a single large ingot)

- A slice of an etched wafer. In this case it appears to be some sort of memory, but the process is the same for a processor.

- Several cut die, these are cut from a wafer after testing. The red dot notes that these particular dice failed one or more of the tested and should be discard. Thats probably why they made it into this kit rather then a saleable device.

- An bare unfinished package. These packages are rarely if ever made by the company making the processor. They are made by companies such as NGK (who also makes spark plugs) and Kyocera. The bottom of the die cavity is usually connected to the ground pin of the package.

- Next is a package with the die placed in the die cavity. No bonding wires are installed in this example but that would be the next step. The very fine gold bonding wires connect the pad ring on the edge of the die, to the pads in the die cavity. Those [ads are connected through the package to the 40 pins of the ceramic DIP package.

- Finally we have a completed device. The lid is usually soldered or brazed onto the package and markings applied. The marking on this example make it a ‘Marketing Sample’ as they are there solely for looks, rather then to identify the device, its date, and lot.

These types of kits were produced for educational use, and given to schools, as well as sales people to assist in marketing Zilog’s various products

January 6th, 2014 ~ by admin

HP 1FZ3-0001 PA7000 66MHz – 1991

Welcome to 2014 and a new year of exciting processors and technology finds at the CPU Shack Museum. We’ll spend the next couple weeks posting some of the more interesting finds of 2013 that didn’t get posted before.

The PA-RISC was HP’s architecture meant to unify all their non x86 processors of the 1980’s. The project began in the 1980’s and produced over a dozen processors designs, ending with the PA-8900 in 2005, though the Itanium borrows heavily from the PA-RISC line. HP discontinued support for PA-RISC servers in 2013 and recently announced that they will discontinue use of the Itanium as well.

Early PA-RISC processors were multi-chip designs such as this PA-7000. The PA-7000 pictured is only the CPU, the FPU was a separate chips, as was the L1 caches (no support for L2 caches). A memory controller was also a separate chip. Made on a 1 micron process the PA-7000 had 580,000 transistors and ran at 66MHz. Early versions had 2 lugs for the heatsink on the package while later versions had only a single lug.

November 1st, 2013 ~ by admin

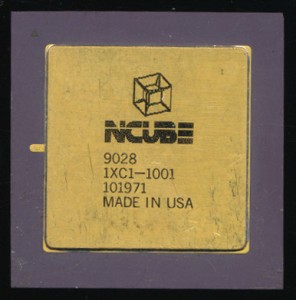

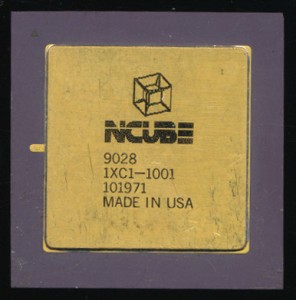

nCube/2 Processor – 20MHz

The logo is a Tesseract – a 4-way Hypercube

In 1983 Stephen Colley, Dave Jurasek, John Palmer and 3 others from Intel’s Systems Group left Intel, frustrated by Intel’s seeming reluctance to enter the then emerging parallel computing market. They founded a company in Beaverton, Oregon known as nCube with the goal of producing MIMD (Multiple Instruction Multiple Data) parallel computers. In 1985 they released their first computer, known as the nCube/10. The nCube/10 was built using a custom 32-bit CMOS processor containing 160,000 transistors and running initially at 8MHz (later increased to 10). IEEE754 64-bit floating point support (including hardware sqrt) was included on chip. Each processor was on a module with its own 128KB of ECC DRAM memory (implemented as 6 64k x 4 bit DRAMs.) A full system, with 1024 processor nodes, had 128MB of usable memory (160MB of DRAM counting those used for ECC). From the outset the nCube systems were designed for reliability, with MTBFs of full systems running in the 6 month range, extremely good at the time.

The nCube/10 system was organized in a Hypercube geometry, with the 10 signifying its ability to scale to a 10-way Hypercube, also known as a dekeract. This architecture allows for any processor to be a maximum of 10-hops from any other processor. The benefits are greatly reduced latency in cross processor communication. The downside is that expansion is restricted to powers of 2 (64, 128, 256, 512 etc) making upgrade costs a bit expensive as the size scaled up. Each processor contained 22 DMA channels, with a pair being reserved for I/O to the host processor and the remaining 20 (10 in + 10 out) used for interprocessor communication. This focus on a general purpose CPU with built in networking support is very similar to the Inmos Transputer, which at the time, was making similar inroads in the European market. System management was run by similar nCube processors on Graphics, Disk, and I/O cards. Programming was via Fortran 77 and later C/C++. At the time it was one of the fastest computers on the planet, even challenging the almighty Cray. And it was about to get faster.

Read More »

October 25th, 2013 ~ by admin

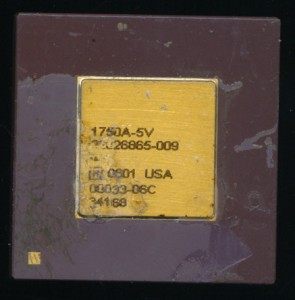

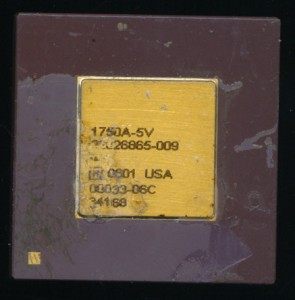

Honeywell 1750A-5V -2008

While its not in the best condition I was still pleased when it came in. MIL-STD-1750A was first developed in 1980 to provide a uniform architecture for military computing, while allowing competition in the market to produce different versions at a hoped for reduced cost. By 1996 though the 1750A was declared inactive for new designs in the US military. It had been widely replaced by other more powerful commercial designs, notably the 80386 and 80486. Many militaries around the world continue to use the 1750A and the US Military continues to need spares.

Honeywell continues to produce the 1750A-5V, a single chip implementation of the 1750A with on-board 40-bit FPU, much like Fairchild’s commercial F9450. Produced on a CMOS SOI (SIlicon On Insulator) 0.65u process the 1750A-5V runs at up to 40MHz, twice as fast as most did in the 1980’s. This particular example was produced in 2008 though Honeywell continues to make and advertise the 1750A.

The radiation hardened version was used on the Cassini Orbiter (now orbiting Saturn), ESA’s Rosetta Comet probe as well as the Guidance computer for the Air Force’s Titan 4 missile.

October 8th, 2013 ~ by admin

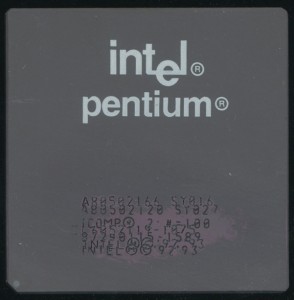

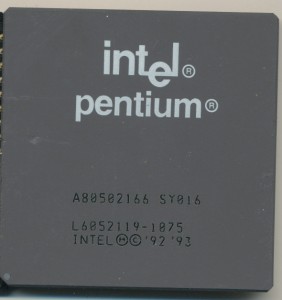

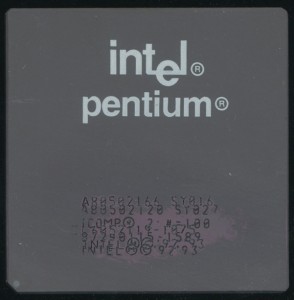

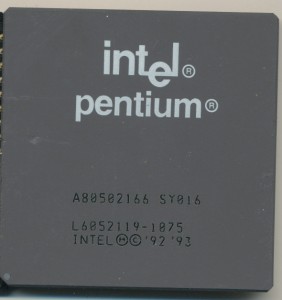

Pentium 166 SY016 Faked from Mobile 120 SY027

Here is an interesting example of what led Intel (and other manufacturers) to start locking down multipliers on their processors as well as adding anti-counterfeiting measures. This processor appears to be a 166MHz Pentium Processor, which in 1997 sold for around $200. A 120MHz Mobile Pentium sold for less than $100. Thus processors of lower speeds were often remarked by unscrupulous dealers and sold as higher speed parts. The forgeries had to be made quick, as processor prices dropped very quickly, the 166MHz Pentium debuted at nearly $1000. Most Pentium fakes were made by painting over the original markings and painting/engraving news ones. Some of the better fakes ground down the old markings first. Nearly all are easy to spot by the trained eye, wrong fonts, date mismatches, etc.

This particular example, from somewhere in 1997, was faked from a Pentium 120MHz mobile to a 166MHz desktop Pentium. As far as fakes go this was a fairly conservative one. Often 166s were faked from 100s or even 75s. The 120 was a 2x60MHz processor running at 3.1V, while the 166 is 2.5×66 (you see why locking the multiplier discouraged faking?) running at 3.3V. This resulted in a 28% overclock at about a 6% voltage increase. In this case the processor likely ran fairly well, if perhaps a bit warm. Some of the more extreme fakes resulted in very unstable systems due to overheating and pushing a processor well beyond what it was designed for.

Before removing paint

Today counterfeit chips are still a major problem, though it was shifted from the consumer market, where prices are generally low, to the military and industrial market, where prices are high, and there is still demand for older devices.